From Fluxus Foundation Archive (2009)

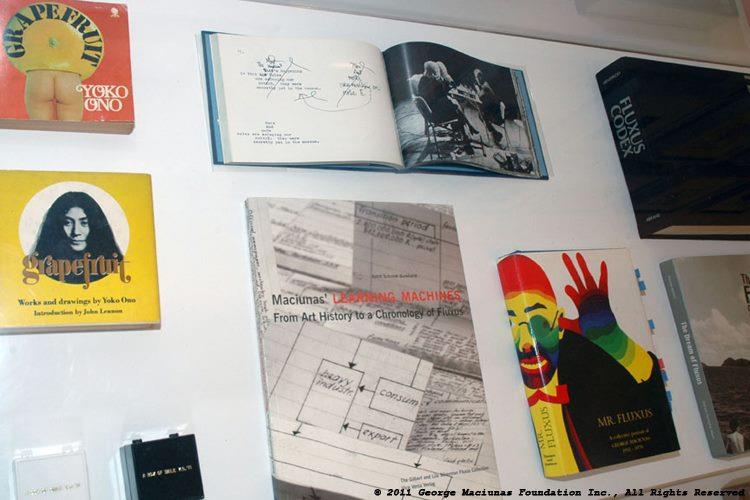

150 pieces comprise the original manuscript of Yoko Ono’s pivotal 1964 work Grapefruit. Assembled into an artist’s book and originally published in Tokyo in a limited edition of 500 (Simon and Schuster would release a mass market edition in 1970), the small, rectilinear cards each contain simple, hand-typed instructions, such as “Imagine the clouds dripping. Dig a hole in your garden to put them in.” (Cloud Piece, 1963) This format, which became a crucial precursor to conceptualism, emerged from the event scores by artists attending John Cage’s Experimental Music Composition classes at the New School in New York—in particular, George Brecht and La Monte Young.

Event scores, invented by George Brecht, are simple directives to complete mundane tasks. To perform Brecht’s 1961 piece EXIT for instance, one would simply exit a doorway. The idea, which recall Happenings with less theatricality, was to highlight facets of everyday life—and more conceptually, critique traditional artistic representation. Similar to a musical score, event scores could be performed and reinterpreted by anyone. These event scores became a key artistic praxis of Fluxus, with numerous artists offering their own interpretations of the medium, including the likes of Ken Friedman and Allison Knowles.

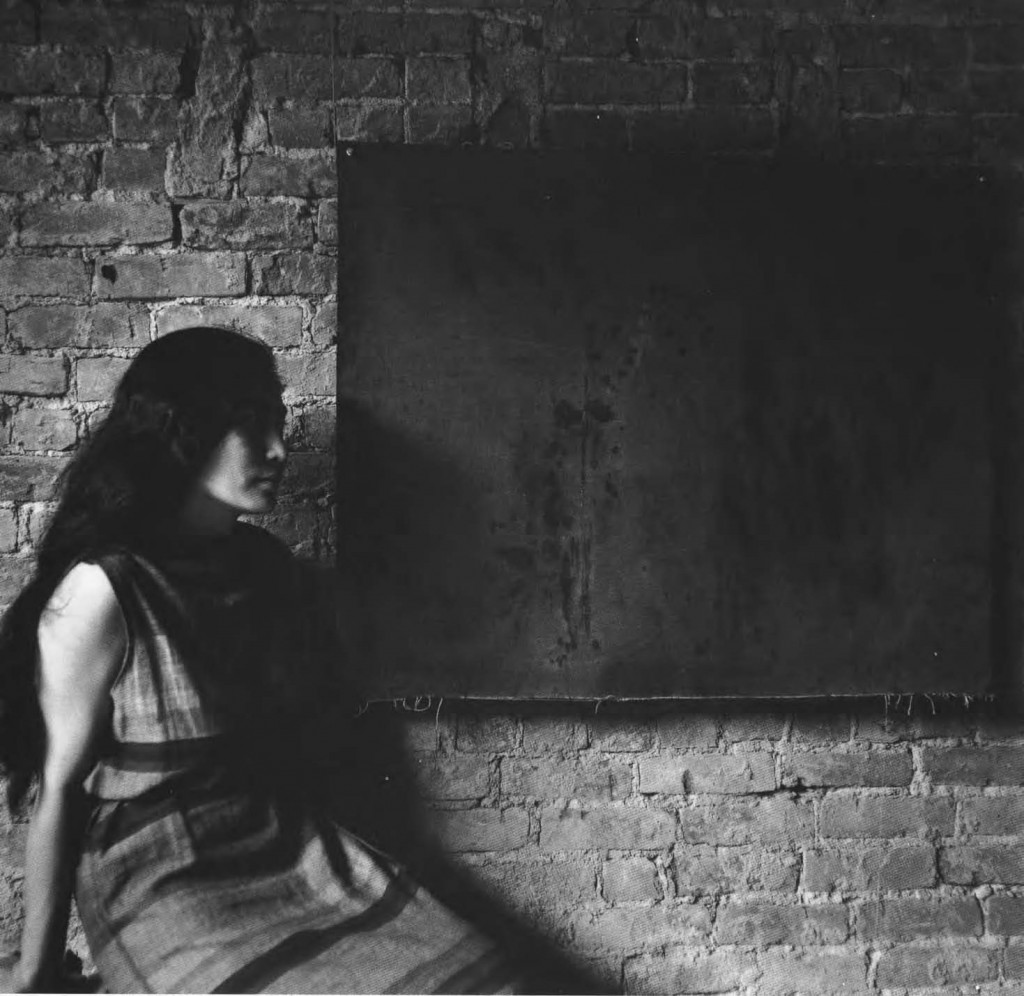

By the end of 1960, Yoko Ono and La Monte Young had begun to host performances featuring emerging avant-garde artists in Yoko Ono’s Chambers St. loft. It was these performances that drew the attention of George Maciunas, who offered Yoko Ono a solo exhibition of her “Instruction Paintings” at his short-lived AG Gallery, located at 925 Madison Avenue, in the summer of 1961. Shortly thereafter, Fluxus was born.

George Maciunas's portrait of Yoko Ono, 1961

Although Yoko Ono’s instruction pieces—some of which were assembled during a brief stay in a sanatorium in Japan following the dissolution of her first marriage—reflect the same format as the Fluxus event scores pioneered by George Brecht, they occupy a separate poetic and imaginative dimension. Brecht’s scores confound the boundaries between text and physical performance, while Yoko Ono’s provoke a more cerebral, illusory performance.

An introductory card from original manuscript reads, “Some of my pieces were dedicated to the following people. Sometimes they were informed of it but mostly not.” The list that follows contains the names of fellow artists, friends, and Fluxus components, from George Maciunas to Robert Rauschenberg, to Isamu Noguchi, to Peggy Guggenheim, revealing the array of individuals who inspired Yoko and consorted within her closest social circle.

The original Grapefruit manuscript is further bestrewn with handwritten notes, reflecting Ono’s whimsy. It is this imaginative use of language that paved the way for the first wave of conceptual artists, including Lawrence Weiner and Joseph Kosuth, to materialize in the 1960s. Perhaps then, Grapefruit can be regarded not only as a seminal Fluxus work and Yoko Ono’s magnum opus, but also the crown jewel of Conceptualism—and accordingly, on a broader level, a paragon of Postwar contemporary art.

Grapefruit second edition on display with other Fluxus research materials at Stendhal Gallery, 2009