Metro George Maciunas

Let’s have some new clichés. – Samuel Goldwyn

The realm of jokes knows no boundaries. – Sigmund Freud

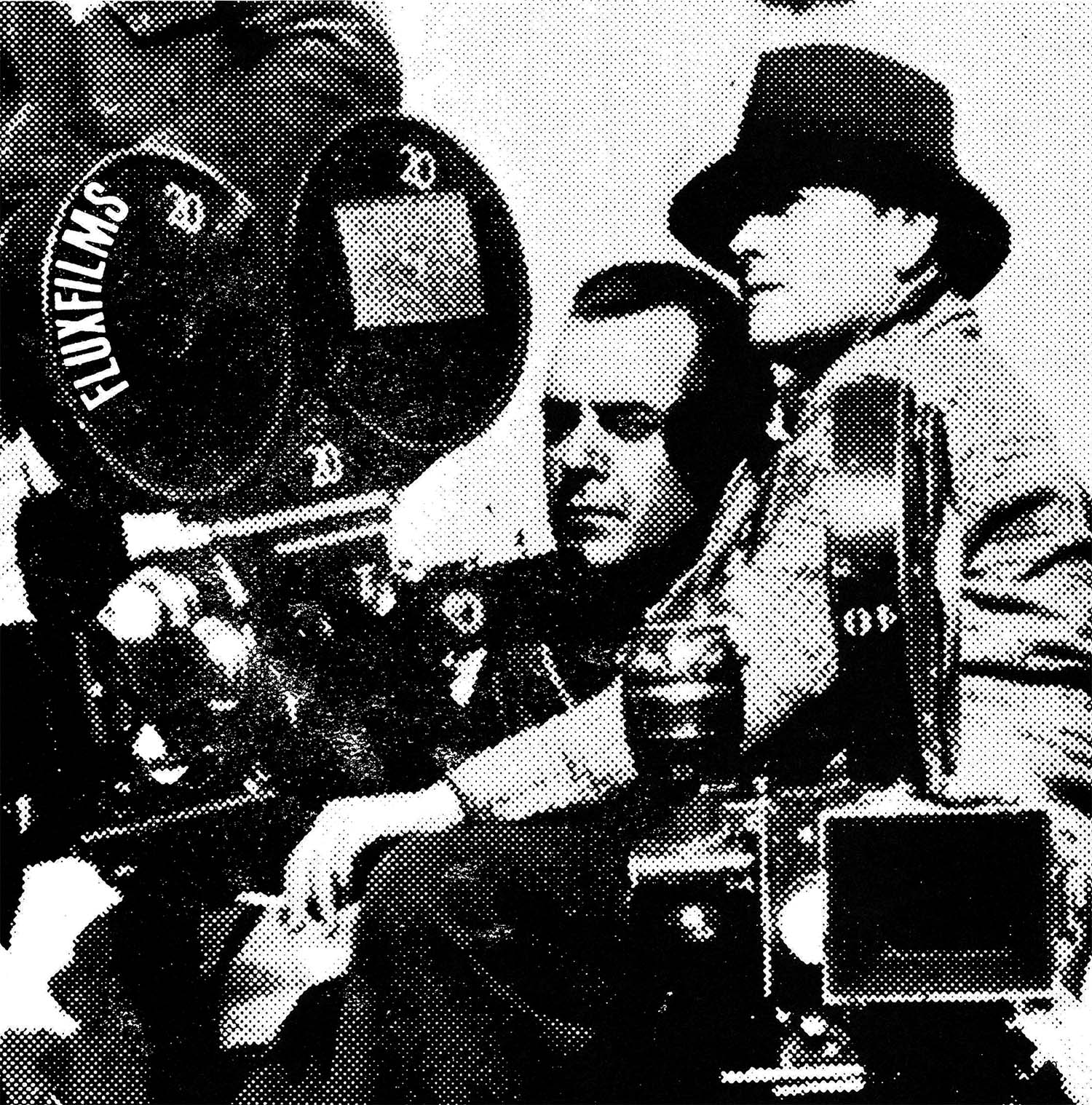

Fluxfilms Label. Designed by George Maciunas.

Fluxfilms Label. Designed by George Maciunas.

There are at least two Fluxus cinemas: one consisting of forty-odd short films, most dating from the mid-1960s; the other, potentially open-ended, embracing virtually any motion picture seen in a Fluxus way.

Maciunas seems to have divided his cinematic attentions between overseeing production on the various reels of Fluxfilms and monitoring the wider arena of Fluxus activity on-screen. Included in the extraordinary paper trail that constituted his real lifework are files on “films liked and noted,” clippings of ads for “Used 8mm Silent” films (including such standards as The Birth of a Nation and Tarzan of the Pes, starring Elmo Lincoln), listing for prints of a wide range of silent comedy (early Chaplins, later Keatons, and even the less heralded work of Chester Conklin, Snub Pollard, and Mack Swain), and a pastiche of offerings for railroad movies, Pearl White serials, war documentaries, and vintage sports films. Found in the same files are mail-order ads (below) for the 8mm viewers, film splitters, reels and cans, and other low-end devices and materials that were employed in the making, packaging, and marketing of the FLuxfilms.

8MM Fluxfilm Loops and 8MM Hand-held viewer.

8MM Fluxfilm Loops and 8MM Hand-held viewer.

Maciunas’ fascination with film and film history – the “prehistory” of the Fluxfilms, as it were- was apparent in the aesthetic genealogies he often crafted for the movement at large. In these graphic time lines charting the cultural milieus and artistic practices he thought to have prefigured Fluxus, Maciunas typically invoked a wide range of film forms – from mainstream “Walt Disney Spectacles” and the comedies of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton to the latest avant-garde works of Ed Emshwiller, Takairo Limura, Ken Jacobs, and Stan Vanderbeek. Like Film Culture, with which Maciunas maintained a long association as a graphic designer, his passion for film was strong enough o embrace both the classic and the contemporary , the studio feature and the experimental shot.

Cinema frequently served for Maicunas as an antecedent art form and at times as a productive metaphor for articulating Fluxus strategies and principles. Films could be invoked to clarify key aspects of Fluxus practice. In an analysis of monomorphic structure – the “single, simple form” that underlay many of the early Fluxus scores and performance – for example, Maciunas cited comic strategies in the film work of Keaton and countered with Marx Brothers (opposite):

Watch Buster Keaton. He’ll never have tow gags at the same time. They follow one another very quickly, but they will not be simultaneous. And if they’re simultaneous, usually they’re bad gags. That’s one reason I think Marx brothers are not that good on gags because they just overcrowd them.But what finally may have linked the cinephilia of Maiucnas to the cultural intervention of Fluxus were the populist roots of film and the central role of humor in both enterprises. The appeal of humor for Maicunas (“I was mostly concerned with humor, I mean like that’s my main interest, is humor”) seems to have been grounded, at least partially, in early cinematic models. Like other anti-art movements in this century, the burgeoning Fluxus enterprise recognized in these popular entertainment not only the aggression endemic to every comedic form but also a distinctly antisocial, antibourgeois sensibility at play in the physical humor, sight gags, caricatures, and parody of classical silent comedy.

As Maciunas seemed well aware, film comedy illuminated an inverted world in which the weak triumphed, hypocrisy was unmasked, and the maintenance of law and order fell onto the sloping shoulders of the blundering cops at Keystone. Comedy’s corrosive external gaze was matched in the work of artists such as Chaplin and Keaton by reflexive strategies that bared formal aspects of the medium. Sight gags revolved around the limited palette of black-and-white filming, spatial distortions intrinsic to the medium’s two-dimensionality, or reversals of motion and direction that derived from shifts in the movement of the filmstrip. These were privileged moments in which the sight gag made visible the mechanics of film and, for a moment, granted us participatory entry into the making of the work.

Of the now movies (mostly silent and black-and-white) that Maciunas commissioned, collected, and often completed under the Fluxfilm imprimatur, many can be described as comedies, and they share with their more mainstream predecessors both an outward parodic focus and an inward reflexive gaze. In Maciunas’ hands, and often punningly literal form in works in which parody is enacted on the material level rather than within a fiction. His brief 10 Feet (Fluxfilm no.7, 1966), for example, transforms the filmstrip into a ruler calibrated to the title ten feet. Similarly, James Riddle’s lengthier study 9 Minutes (Fluxfilm no.6, 1966) shifts the screen into a flashing digital clock that progresses second-by-second for its titled duration. In End after 9 (Fluxfilm no.3, 1966), an unattributed short made by Maciunas, the title not only predicts the content but, in a comic reversal of the relationship between text and title, also makes up the main portion of the film, which ends after a split-second montage of the numbers one through nine. Even Yoko Ono’s politically engaged No.4 (Filmfilm no.16, 1964/1965) maintains a punning relationship with the medium. While its title is suggestive of Maciunas’ purely functional numbering system, the Four proves a remarkably perspicuous figure in describing the content of the film – series of buttocks in motion shot in close-up to create mobile compositions of quartered biomorphic masses.

A fuller figure of the performer emerged in a subgenre of “comedies” that embraced the more performative aspects of Fluxus. In the silent film Shout (Fluxfilm no.22, 1966), attributed to Jeff Perkins and photographed by Yoko Ono, the filmmaker squared off with fellow artist Anthony Cox in a shouting match that – is comically incomplete. The relationship of performance to the visual boundaries of the medium is wryly explored in the untitled Fluxfilm no.36 (1970), made by the Australian artist peter Knnedy and Mike paar. Here, a performer is visible only below the ankles against a backdrop of bare floor seen from directly overhead. As the feet slowly begin to edge clockwise around the frame of the film, we hear the coaching directions (“Lovely, keep going”) of an offscreen partner, who assists in the completion of this circuit. Not unlike Marcel Duchamp’s critique of the medium in his film Anemic Cinema (1926) (consisting of rotoscopes embossed with nonsense texts that alternate with depth-producing spiral forms), the film creates a ludicrous spectacle of the conflation of the space of performance with the material limits of the film frame.

The target of Fluxfilm humor, however, was often directed less at the medium in general or the social order per se and more at the hierarchies internal to the contemporary art world – especially the deadly earnest, serous film culture represented by the leading form of avant-garde filmmaking of the day, the personal and poetic (or, more properly, “mythopoeic”) cinemas of artist such as Kenneth Anger, Bruce Baillie, and Stan Brakhage. These anti-art-film strategies employed by the Fluxfilms were multiple; they ranged from jettisoning the personal or visionary content of the poetic films to dispensing with significant aspects of their formal innovations, particularly the complex editing schemes and expressive cinematography that marked the intervention of the personal into this most impersonal of media. In place of personal content, the Fluxfilms countered with the institutional, the functional, and/or the minimal. Some of the films, such as Nam June Paik’s Zen for Film (Fluxfilm no.1, 1962/1964), made of a roll of clear leader, or John Cavanaugh’s flickering Fluxfilm no.5 (1965), eliminated the image completely; others, the “readymades” such as Robert Watts’ moving X-ray study Trace No.22 (Fluxfilm no.11, circa 1965) or Alber Fine’s loop of a color test strip in Fluxfilm no.24 (1966), consisted solely of found footage. Maciunas himself developed one of the more effective means to make “cameraless” movies by applying art type directly onto the filmstrip (as in his Artype, Fluxfilm no.20, 1966). Still others – Joe Jones, Yoko Ono, and Mieko(Chieko) Shiomi – subverted the motion of motion pictures by producing unedited, fixed-frame, slow-motion portraits of mundane activities.

Less formal but more parodic in its humorous assault on the poetic impulse was Dick Higgin’s sole film for FLuxus, Invocation of Canyons and Boulders for Stan Brakhage (Fluxfilm no.2, 1963). The title punningly invokes two avant-garde filmmaking icons: Brakhage, through the double designation of his name and adopted hometown, Boulder, Colorado; and Baillie, by reference to his hometown, Canyon, California, and his independent film-distribution service, Canyon Cinema. In a perverse variation of both Brakhage and Baillie’s strikingly visual, highly personal autobiographical mode- a neo-Romantic exploration of the inner psyche that venerates the external gaze of the camera (and sets in motion the “I/eye” paradigm of visionary filmmaking) – Higgins films himself simply in facial close-up in the act of chewing. While only a few seconds long, and consisting of a series of extremely close-ups of his masticating mouth in motion, the film was made to be shown in endless looped versions. According to one account, “Higgins’ movie…started at 8 p.m. and 1 a. m., when I left, it was still running.”

Jackson Mac Low’s 1961 score for the unrealized Fluxfilm Tree* Movie similarly parodied the romantic imagery of the poetic film while challenging the claims of personal authorship and the visionary experience. His film score (not unlike other early Fluxus event scores) involved a simple three-step production:

Select a tree*. Set up and focus a moive camera so that the tree* fills most of the picture. Trun on the camera and leave it on wihout moving it for any number of hours. If the camera is about to run out of film, substitute a camera with fresh film. The tow cameras may be alternated in this way any number of times. Sound recording equipment may be turned on simultaneously with the movie cameras. Beginning at any point in the film, any length of it may be projected at a showing.*) for the world “tree,” one may substitute “mountain,” “sea,” “flower,” “lake,” etc.

Maciunas embraced this impersonal encounter between the camera and the natural world and included the idea for the Mac Low feature among his earliest proposed festival of Fluxfilms, advising presenters to “just film form tripod a tree for an hour or so.” Mac Low’s work, along with the Higgins film, later served Maciuans in a critique of another major avant-garde film practitioner of the period, Andy Warhol. As Maciunas complained: “[Warhol’s] Sleep, 1963-4”… to begin with is a plagiarized version of Jackson Mac Low’s Tree Movie, 1961 just as his Eat, 1964 is a plagiarized version of Dick Higgins’ Invocation.” Whether or not he was inspired by Mac Low’s concept, Warhol’s underground movies of the mid-1960s and the experimental films of FLuxus existed in mutually exclusive arenas. Despite formal similarities and a shared contempt for the poetic cinema, Warhol’s work, produced in the context of Pop Art, was predicted on voyeurism and the fetishistic power of the moving image, while a film like Tree* Movies was rooted in a desire to dematerialize the medium in ordr to bridge the gap between art and life. And , of course, most notably, Warhol’s work actually was realized; Mac Low’s did not event need to be.

The decentralization and democratization of the production process implied by Maciunas’ approach to presenting (and creating) Tree* Movie represented a transgression of the highly individualistic, personal, and handcrafted “style” of then-current avant-garde practice. For Maciuans, film was-much as the critic Walter Benjamin had described it nearly three decades earlier- the archetypal mechanically reproducible medium and, as such, an ideal medium for the multiple. Like the array of plastic boxes that served as supports for the Fluxus edition of games and scores, paperwork’s, and appropriated readymades, the celluloid-based medium embodied in its own material origins the industrial, impersonal facticity of the age of reproduction. Or to put it in more practical terms, with film, Fluxus art could be produced literally by the yard.

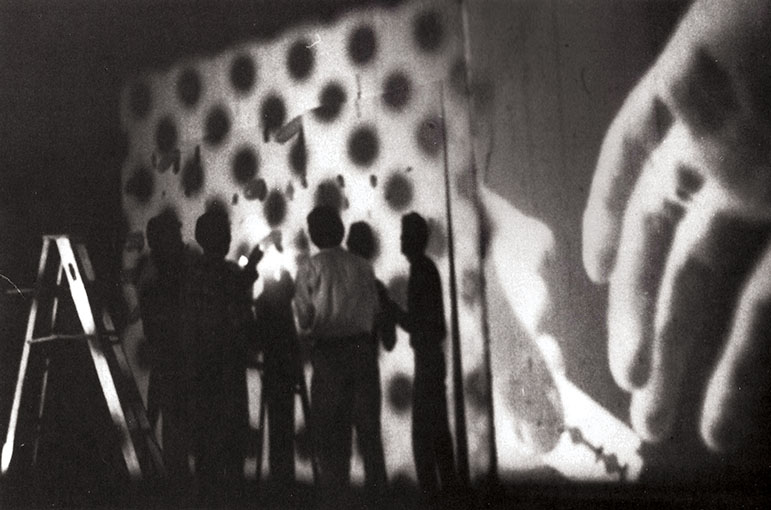

Tied to these unorthodox productions were equally unconventional distribution plans and modes of exhibitions. Maciunas intended many of the Fluxfilms to be cut into small-format (8mm) loops for inclusion in Fluxyearboxes or inexpensively sold along with handheld viewers. Others were produced in various static forms. These were printed as serial stills, as with Higgin’s Invocation…, or proto-flip-book imagery (dubbed “poor man’s movies”), as with Shiomi’s Disappearing Music for Face (Fluxfilm no. 4, 1966)- and marketed along with the boxes and scores. Still others were designed to be “expanded in to multimedia environments replete with design plans and suggested sound components, all under the rubric of Film Wallpaper. While plans for such room-sized projections appeared frequently in Fluxs publications and newsletters, the only documented presentations of such pieces were a two-screen projection by Pual Sharits (1966) and a smaller, “capsule” version in a three-foot cube created for the FLuxfest presentation of John Lennon and Yoko Ono in 1970.

The role of the individual Fluxus artist was diminished by these production and presentation methods, but Maciunas’ involvement remained very much hands-on. He rented the camera equipment, purchased the film stock, shot the title sequences, placed the lab orders for prints and paid the bills, spliced together the programs, and personally prepared and mailed prints to film festivals in the United States and Europe. It was his numbering system that identified the films and his imprimatur that could either embrace or exclude the work from Fluxus. He ordered and reordered the versions, creating a packaged short program and a companion selection that extended it to feature length.

Despite his efforts, the films received only scant critical attention and limited public screenings. The 1965 Ann Arbor Film Festival, the venue Maciunas had selected for the first public screening of a short program of Fluxfilms, accorded the artist and their work recognition in the form of the Moss Tent Award, a lightweight, high-count poplin mountain tent. Other minor awards followed, including the Tracy Atkinson Award of fifty dollars form the Milwaukee Art Center and modest fees for screening at a few university and film-society venues. Maciunas loaned a print to the Fluxus artist Ken Friedman for West Coast screening, shipped another to Milan Knizak in Prague, and eventually deposited a long and a short program with the Film-Makers’ Cooperatives in New York.

Critical recognition for the Fluxfilms was forthcoming neither from the champions of the cinematic avant-garde nor from mainstream reviewers: the former regarded the work as “subversive,” and the latter regarded it not at all. The only significant acknowledgment of the work and of Maciunas’ central role as the producer of Fluxfilms during this period cam in the fall of 1968 from the Friends of New Cinema, an organization that provided experimental filmmakers with small but strategic funding. As the award letter stated,

The Friends of New Cinema has undertaken to award a grant for your support and encouragement in your work in experimental films. The Friends expect to be able to send you the sum of $40.00 per month for the period of twelve months…. Best wishes for your continued good work.Enclosed was a check for forty dollars made out to George Maciunas.

Published in catalogue IN THE SPIRIT OF FLUXUS © 1993 Walker Art Center.