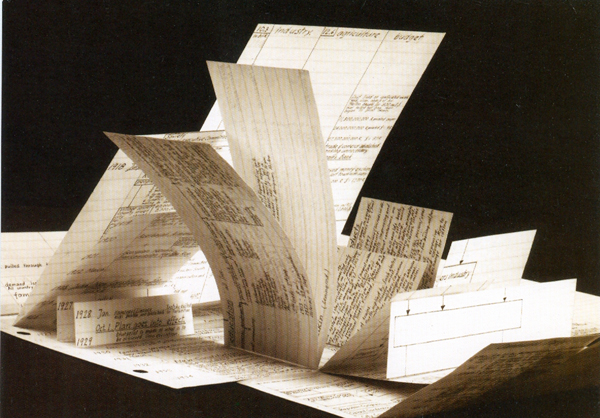

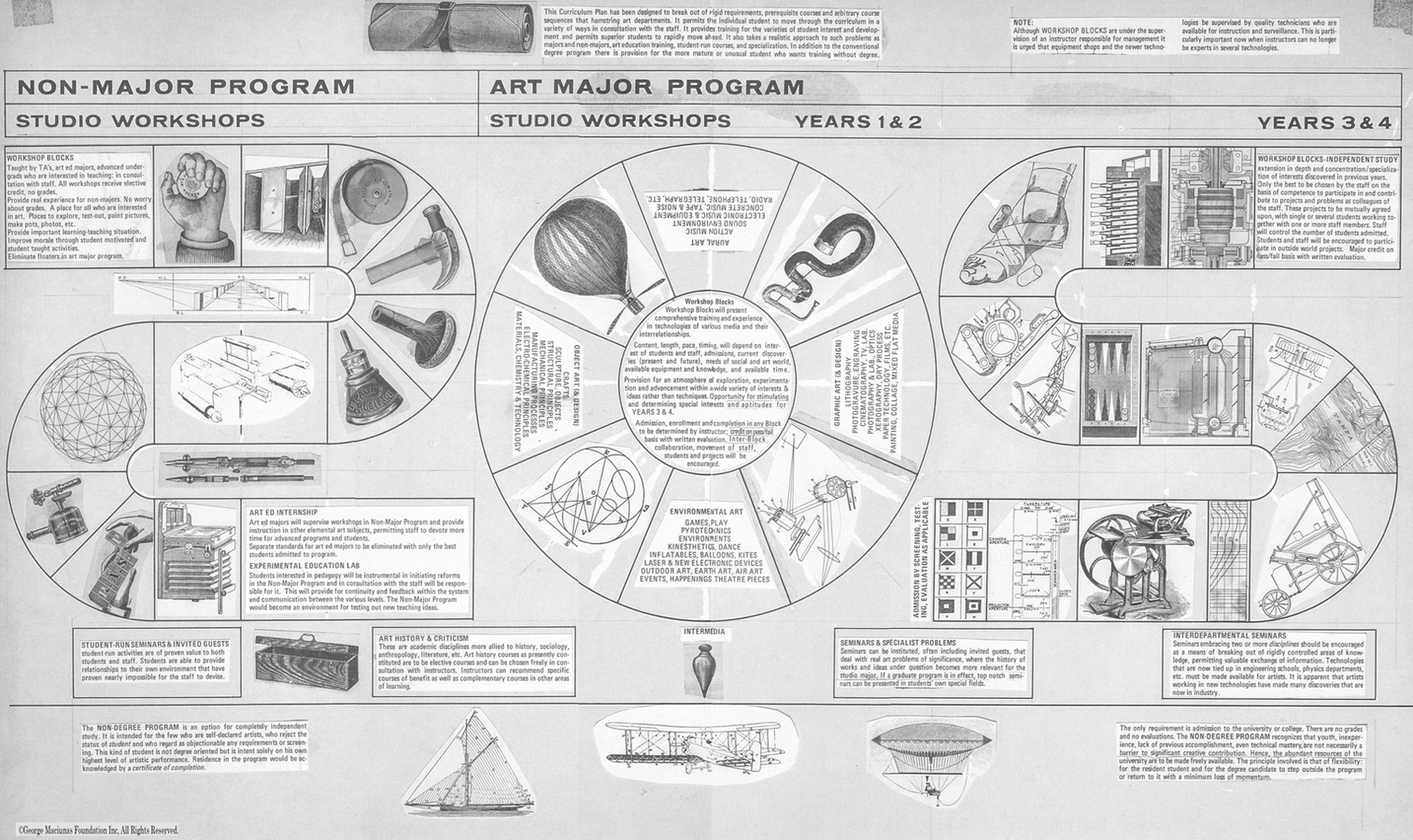

Compared to many artist colleagues of his generation, Maciunas’ education was far-reaching. He had studied art, graphic design, and architecture at the Cooper Union School of Art in New york (1949-52), architecture and musicology at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh (1952-54) and, finally, he gained a sound knowledge of art history at the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University (1955-60), focusing on European and Siberian art of the mass migration period. (1) As was the norm for American students at that time, Maciunas also composed schemes and lists of data and facts, which granted him a better overview of greater developments. Maciunas was an exceptional learning machine. During his studies he also occupied himself with languages, logic, psychology, and physiology. His broad range of interests and his universal approach required appropriate forms of knowledge management so as to keep stock of his wide-ranging material, The diagram form lent itself to ordering facts, reducing complexities, and proffering meaning. With it, the ever expanding field of knowledge was made manageable within a limited time, as Maciunas recapitulated in his Preliminary Proposal for a 3-Dimensional System of Information Storage and Presentation.(2) In this short text, written in the late sixties, Maciunas condemned the inefficiency of the American education system, which for him lay in premature specialization and fragmentation of knowledge. Maciunas knew what he was talking about. After all, he had studied for eleven years at college and university, much longer than average, and had sufficient experience at several renowned educational establishments. his diagrammatic summaries of his proposals for improvements came much later though, with the Learning Machine in 1969. With this chart-like taxonomy. Maciunas harshly criticized the slow linear-narrative method of traditional information media like books, lectures, TV, or films. Maciunas, who did not really enjoy reading books, replaced text-oriented knowledge transfer with a visual system of information. He had a three-dimensional plan of knowledge in mind, which was to be particularly useful in offering a time-saving overview. Even if Maciunas’ Learning Machine concept, as a complete view of all areas of knowledge, did not get beyond a two-dimensional tree of categories, it still provides a binding criterion with its interdisciplinary frame of reference. Networked thinking is intended to help us not to lose sight of greater contexts, and this is the only way to overcome the limits to insight caused by specialization . Students with a sound general education should be offered a four-year curriculum which would allow them to specialize only gradually. Within the framework of these reform proposals, Maciunas also advocated interdepartmental seminars from which the art major program could profit considerably. He feared that the chances of budding artists for professional survival would otherwise sink drastically. The gravity of the situation was expressed in Maciunas’ Curriculum Plan with the Typographic SOS call.

-

(1) Maciunas’ mentor at N.Y.U. was the art historian and Asia specialist Alfred Salmony. He might have aroused Maciunas’ interest in non-European art in general and in the exotic motive of the long tongue and its apotropaic character in particular. See Alfred Salmony, Antler and Tongue: An Essay on Ancient Chinese Symbolism and its Implications (Ascona 1954), pp.30-48. Maciunas made the extended tongue which can be seen on the Aztec calender or sun stone, into a meaningful emblem of Fluxus.

(2) See George Maciunas, “A Preliminary Proposal for a 3-Dimensional System of Information Storage and Presentation,” in Proposals for Art Education from a Year Long Study Supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York 1968-1969 (San Francisco 1970), pp.24-26 (p.24).

-Astrit Schmidt-Burkhardt